CS 3710

Introduction to Cybersecurity

Aaron Bloomfield (aaron@virginia.edu)

@github | ↑ |

SQL, XSS, & CSRF

SQL Primer

SQL Primer

- SQL - Structured Query Language - is a formally defined language

- ANSI formalized first in 1986

- Latest version is SQL:2016

- There are many companies and products that create a database that uses SQL

- Microsoft Access, Oracle, MySQL, PostgreSQL, etc.

- The level of SQL we will be studying will apply to all of these

SQL Basics

- SQL data is stored in tables, similar to spreadsheets like excel

- Each row is an entry, and each column has a type

- This table on the next slide has types: string, string, string, integer

SQL Table

| Last name | First name | Userid | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smith | Isabella | ias1s | 1 |

| Johnson | Jacob | jbj2t | 2 |

| Williams | Emma | ecw3u | 3 |

| Jones | Ethan | edj4v | 4 |

| Brown | Olivia | oeb5w | 1 |

| Davis | Michael | mfd6x | 2 |

| Miller | Sophia | sgm7y | 3 |

| Wilson | William | whw8z | 4 |

SQL commands: select

- You can retrieve all the table’s data:

- You can select only specific data:

SQL select command output

- The output is in the format of a text-based table:

SQL commands: update

- To change a single entry:

- To update all entries

SQL commands: insert

- To create a new entry:

- An alternate form:

SQL commands: delete

- To delete a single entry:

- To delete many entries:

- To delete all entries

Other SQL commands

show databases;- Shows which databases exist that the user can access

use <db>;- Changes to a different database

show tables;- Shows which tables are in the current DB

describe <table>;- Gives details about the table columns

Other SQL commands

drop database <db>;- Deletes an entire database (and all the tables in that DB)

create table <table> [...];- Creates a table

create database <db>;- Creates a database, which can hold an arbitrary number of tables

grant [...];- Sets (‘grants’) permissions on a database to a given user

Other SQL commands

truncate <table>;- Erases all the data in the table

- Almost the same as ‘delete from course;’

drop table <table>;- Deletes an entire table (and all data!)

SQL Injection Attacks

Vulnerable script for SQL injections

- Let’s imagine that your web script asks for your userid

- Then does a select command on that value

- Pseudo-code:

var userid = getUseridFromWebForm()

var query = "select * from course where userid='" +

userid + "';"

var result = databaseQuery (query)

doSomethingWithTheResult (result)- This has a SQL injection attack vulnerability

- Next, we’ll see an exploit

Normal operation

- If we enter ‘asb2t’ into the web form, we will get the following SQL command:

- Which works as desired

SQL injection attack exploit

- What if we enter the following as our userid:

- At that point, our SQL command is as follows:

- Which does not work as desired

SQL injection attack exploit

- Our SQL injection attack query:

- The DB will perform two database operations (a select then a delete), and then see a comment at the end of the statement

- The DB function the script calls might return a value or it might not

- At this point, we have deleted everything from the table

SQL injection attack exploit

- This is not stealthy - the DB probably won’t work right if everything has been deleted

- We can put in various commands to modify the database, or access data from it that we would not be able to access otherwise

- Typically, the privileges that a script runs allow full read/write access to the entire database

- We can obviously put more nefarious commands in the injection attack as well

- drop table, drop database, etc.

SQL injection attack prevention

- How to prevent against this?

- We need to escape our input string

- If our input is the same:

- An escaped input string would result in:

- This will search for an odd username, but it will not allow an injection attack

SQL injection attack prevention

- Some (modern) web scripting languages do this automatically

- In PHP, any input string is automatically escaped

- You need to call

stripslashes()to remove them

- Not all languages do this, though

- Perl, C/C++, Java, etc.

- But many provide functions, such as addslashes(), to do this very easily (but not automatically!)

SQL escaped strings

- There are four characters that need to be escaped for safe string handling:

- Single quote (as it can start/end strings)

- Double quote (as it can start/end strings)

- Backslash (as it can change the meaning of the next character)

- NUL byte (as it can signify the end of a string)

- Other languages may have additional character(s) that need escaping

Better SQL attack prevention

- Escaping strings will prevent the attacks, but not much else

- It’s error-prone, because it is easy to forget to do this

- Proper prevention means validating the input

- Checking that it is a proper userid

- Check it against a regex for userids!

- If not, then trigger an error response

- And log and notify that error response!!!

- Checking that it is a proper userid

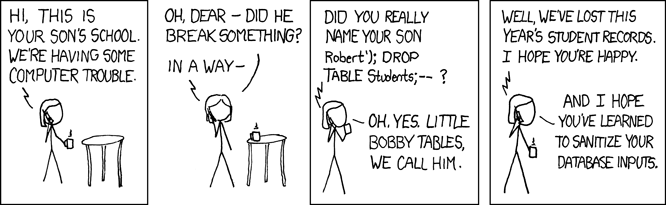

xkcd # 327 on SQL injection attacks

Exploits of a Mom

A clever hacker tries to clear his/her record…

From hackaday.com

Real-world examples

- From Wikipedia

- Oct 15: 156k customer’s personal info was stolen from a British telecom company

- Aug 2014: Milwaukee computer security company had info on 420k websites stolen

- March 2014: At Johns Hopkins, servers in BME had personal info on 878 faculty and students stolen

- I think the article gave up keeping track of after 2014/2015…

HTML and Javascript Primer

A very basic web page

A very basic web page

Specifies the HTML document version

Beginning of the HTML text

Beginning of the head section (contains document info, but not the document content itself)

The title of the document

A very basic web page

End of the head section

Beginning of the body section (contains the actual document text)

The (one line of) document text in paragraph tags

A very basic web page

End of the body section

End of the HTML text

Javascript in web pages

- Javascript (no relation to Java) has C-like syntax, and is used for rich client-side functionality

- To put a Javascript program in your web page:

- Or:

Long URLs

- You can embed form data into a URL:

- http://www.google.com/search?q=aaron+bloomfield

- This is quite common, and is often desired functionality

- (this is actually GET data, not POST data, but we’ll ignore the difference here)

HTML comments

- Any block that starts with

<!--and ends with-->is a comment

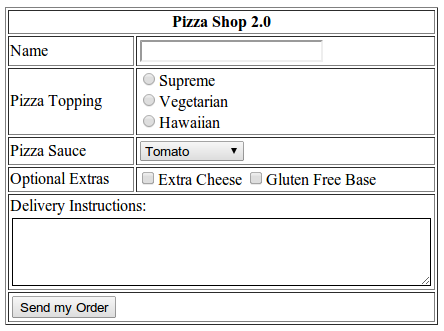

Forms

We’ve all seen HTML forms:

<form action="/action_page.php">

First name: <input type="text" name="firstname"><br>

Last name: <input type="text" name="lastname"><br>

<input type="submit" value="Submit">

</form> - Allows one to request multiple data elements from the client

\(<\)form\(>\) tag

- Attributes:

action="/action_page.php": specifies the script to receive the form datamethod="post": how the data is sent- GET means it’s a long URL: http://server.com/foo.php?username=abcd&password=123

- There are limits to the data size sent

- And lots of security issues for sensitive data

- POST means it’s sent, but not in the URL

- GET means it’s a long URL: http://server.com/foo.php?username=abcd&password=123

enctype="multipart/form-data": if you are uploading files or attachments

HTML Form Widgets

Lots of different ones (image from OpenTechSchool):

There are also hidden input fields:

Cross-site scripting (XSS)

Background: same origin policy

- Web browsers only allow one script to access data from another script if the scripts:

- Are on the same domain

- Use the same protocol

- Use the same port

- This prevents a malicious script from accessing the data from another script

XSS Vulnerable Scripts

- Let’s envision a very simple web script

- It asks you for your name in a web form text field in a web form

- It takes that name, and displays a page that just says “hello, name!”

- While this is an (intentionally) very simple situation to show how XSS works, much more complicated ones exist

- Ebay, where you enter your search string

- Financial institutions, where you also enter a search string

The ‘basic’ web page, updated

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Basic web page</title>

<script>

var balance=1;

</script>

</head>

<body>

<p>Hello Aaron!</p> <!-- name from user input -->

<p>Your account balance is

<!-- newly added code follows -->

<script>

document.write(balance);

</script>

</p>

</body>

</html>Output: Hello, Aaron! Your account balance is 1

Using long URLs

- Perhaps the previous page can be obtained via:

- (not a real site, of course - notice the TLD is wrong)

Exploiting the XSS vulnerability

- Instead of our name of ‘Aaron’, we will input the following as our name:

- Note the necessary returns in the text (

\n), which can also be represented as ‘%0a’ - Some browsers will work with the “” part removed entirely

The HTML page afterward

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Basic web page</title>

<script>

var balance=1;

</script>

</head>

<body>

<p>Hello <script>

balance=1000000;

</script>Aaron!</p>

<p>Your account balance is

<script>

document.write(balance);

</script>

</p>

</body>

</html>Output: Hello Aaron! Your account balance is 1000000

More complicated XSS attacks

- If a decision is based upon said balance, then the decision point can be changed

- Not likely that such a decision will be decided client-side

- Perhaps you can inject code to view cookies or session variables

- But these are easily discernible through the browser anyway

- So we need a reason do perform such an exploit…

Long URLs

- Assume the page we developed can be obtained via:

- http://www.nowhere.abc/printinfo.php?name=Aaron

- Then why can’t we do the following?

http://www.nowhere.abc/printinfo.php?name=<script>\nbalance=1000000;\n</script>Aaron

- That has some non-standard characters (spaces, quotes, returns), but we can fix those

An XSS attack in a long URL

- We replace the punctuation with their web encodings:

- with %0a

- space with %20

- ! with %21

- - with %2d

- / with %2f

- etc.

- Some are definitely necessary, others are just in case they are necessary

An XSS attack in a long URL

- Our new (and rather long) URL:

- http://www.nowhere.abc/printinfo.php?name=%3cscript%3e%0abalance%3d1000000%3b%0a%3c %2fscript%3eAaron

- http://www.nowhere.abc/printinfo.php?name=%3cscript%3e%0abalance%3d1000000%3b%0a%3c %2fscript%3eAaron

- This contains an XSS attack in a URL!

How to create an XSS exploit

- Download the HTML page, and save it locally

- Enter the script manually, and make sure it works

- Then, encode the script using URL-encoded text

- There are online utilities to do this, such as the one at https://meyerweb.com/eric/tools/dencoder/

- Pass that to the web page

- Note that trying to edit the Javascript code through the URL-encoded text won’t work!

XSS exploit payloads

- An XSS exploit can be a URL link that somebody clicks on (perhaps via e-mail) that goes to bankofamerica.com, and…

- Reads the account number and/or balance into Javascript variable(s)

- Sends that data to a remote server

- This can be done via XMLHttpRequest(), which is the function used for Web 2.0 functionality

- Alternately, it can be used to steal cookies, which can allow an attacker to impersonate a victim

An XSS attack scenario

- Alice often visits Bob’s website, where sensitive information is stored.

- Mallory observes that Bob’s website contains a reflected XSS vulnerability.

- Mallory crafts an exploit URL, sends to Alice, and entices her to click on it

- This URL is for Bob’s website, but contains Mallory’s malicious code, which the website will reflect (execute).

- Alice visits the URL provided by Mallory while logged into Bob’s website.

An XSS attack scenario

- The malicious script embedded in the URL executes in Alice’s browser, as if it came directly from Bob’s server

- This is the actual XSS vulnerability.

- The script can be used to send Alice’s session cookie to Mallory.

- Mallory can then use the session cookie to steal sensitive information available to Alice (authentication credentials, billing info, etc.) without Alice’s knowledge.

- Reference

Defenses

- Treat data as data, and escape it!

- Use web frameworks or modern PLs that do this for you

- There are many minute details to get right; see here for details

Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF)

CSRF

- Take a site you are logged into (facebook, bank, etc.)

- Imagine a malicious form posting (or GET request) that is hidden in another link that you “accidentally” click

- That form posting has you do something malicious: transfer money, upload file, like a comment, post to your wall, etc.

- How does the site know that the form posting came from itself and not a malicious link that was “accidentally” clicked on?

CSRF example

- An example link:

- One can imagine a form as well (that is not on site.com):

<form action="https://site.com/post.php" method="post">

<input type="hidden" name="title" value="abcd">

<input type="hidden" name="content"

value="Lorem.ipsum">

<input type="submit" value="Submit">

</form> - This form will only show a submit button, which can be disguised via CSS to look like anything

The need for CSRF

- We need to be able to prevent another site from forging a form posting request

- Solution: we’ll add a token to the form, and check it upon submission

- That token is sent over the HTTPS (i.e., TLS encrypted) connection, so any eavesdropper won’t be able to see it

HTML form with a CSRF token

This is based on the form from the HTML and Javascript primer section:

CSRF Requirements

- The server needs to keep track of which token it sent and to who

- The who is likely an (authenticated) user at a given IP address

- Or maybe based on cookie (which may be tied to an IP address)

- Modern web frameworks do this for you

- The csrf token from the previous slide was based on what Django provides

Comments

//, it is a comment until the end of the line